EUPavilion

Eight proposals for the first European pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Armature GlobaleIT

A Gallery

,

BB with Tomaso De LucaIT/DE

Contenitore europeo

,

From 1957 onwards a series of treaties established what we know today as the European Union. This continental power is a unique case of a progressive peaceful merge of diverse communities linked rather tenuously by traditions, culture, and ethnic backgrounds, but extremely interdependent economically. If the ideological and political architecture of the Union devised by Altiero Spinelli in his Ventotene Manifesto remains largely unfulfilled, the EU still managed to successfully achieve a shared legal and policy framework for the continent.

The most visible part of this framework is the one establishing standards for products and goods made and imported by EU states: this internal structure has had a fundamental effect in shaping the quality of goods and services worldwide, positioning Europe as a powerful regulatory body.

Having to design a speculative pavilion for the European Union at the Venice Biennale we wanted to manifest this cultural context architecturally. We saw the rigid proportional and construction systems of Mediterranean classicism as an interesting precedent for a de-facto shared framework that existed in diverse architectural cultures in Europe a thousand years before the European Union. We looked at products made in the EU such as shipping containers, which embody the normative standardization enacted by pervasive European legislation. We saw a direct link, both formal and conceptual, with what is understood as Classicism in architectural theory.

Classicism is essentially a way to design buildings according to a shared ‘code’ which prescribes the relative holistic dimensioning of building parts to achieve at the same time harmony and buildability. This ‘code’ is what for a 1000 years ensured the perceived ‘beauty’ of classical architecture. We asked ourselves if a banal shipping container, whose form is dictated in a similar way by a code, can be regarded as beautiful and moreover be elevated to a symbol of the European Union in a culturally meaningful context such as the one of the Venice Biennale. In what way a shared culture produces at the same time a legal and architectural ‘code’?

Obviously (with a good dose of idealism) we didn’t want to reduce the EU to a legal code turned into an architectural ready-made, but rather took it as a starting point for the collaboration. The artist Tomaso De Luca has been making sculptures using architectural elements and whole buildings as syntactic material to compose them. His methodology contradicts the idea of architecture as a code and rather presents it as a product of invention, a collage of parts producing an inspired whole. Tomaso worked on the space within the containers, making three-dimensional floor/landscapes made of scraps and cut-outs of studio materials: the simple rectangular volumes were hacked by an assemblage of stairs, inclined planes, and small constructions that opposes the modernist obsession with the project and universal design, and replaces it with a rhapsody of architectural instances, envisioning a complex environment to support the main function of a Pavilion: to make exhibitions, away from the faded paradigm of the white box.

Jasmina CibicSI/UK

A scenographic backdrop for transnationalism

,

Exhibition pavilions devoted to national presentation have been actors performing stagecraft mechanisms for more than a century. However, they still prove to be relevant perturbing organisms, whether they are realised as sites of political action or social complicity with populist tendencies. As such, they are of extreme interest to the contemporary spectator as well as the identity crisis of the current socio-political sphere.

Our temporality brings about the realisation that the third attempt of transnationalism in Europe is failing: the idea of a united Europe has been fractured; and through this realisation we are only now seeing how Europe has since its conception lacked a representative; a recognisable and solid scenographic backdrop – a panopticon device that could visually represent what the idea of a united Europe tried to achieve; foregrounding the notions of transnational solidarity and peace.

It is only when we see our presence break with fissures of uncertainty, that we look to the past; perhaps this is a phycological mechanism whose aim is to make us believe that the past was more violent and chaotic than our presence. The patterns of historic failures can become an invaluable tool for the production of new attempted resolutions and optimism.

The relationship between transnational organisations, federations, and unions with their architectural framework has always been complicated and complex, to say the least. Perhaps the oldest and most illustrative case study within the European ground of this train of thought is the Palace of Nations in Geneva. This mastodont project by the League of Nations collected over 370 proposals by renowned architects, only to then step back when diplomats and politicians realised there cannot be one sole architect involved; namely, they could not choose a single nationality to represent what was to become the parliament of the world; and the space of action that was to prevent another world conflict such as the first World War. The committee went on to select 5 architects who they deemed best within the initial competition. They presented them with a brief to redraw the plans in unison. Needless to say - the time this consortium of egomania took to bring a consistent solution to fruition – took as long as the next world conflict took to arise; the realisation of the Palace concluded only months away from the second World War – which the League was set to prevent.

But it is the case study of the only fully realised disappeared transnational attempt within European ground - which I believe can prove of great potential for a rethink and a warning to what happens when political styling of transnational culture and soft power takes over the relationship between the citizens and the state. I am speaking of course of former Yugoslavia and its post-second World War aesthetic turn which was to clearly position the country as clearly cut from Soviet style as well as the Americanised West. Yugoslav Modernism is perhaps the closest example of unison between stagecraft and statecraft, which so many patriarchal power verticals argued for – especially in the 2nd half of the 20th Century.

And as with dead artists – it is similarly much easier to trace the historical narratives with dead states than those living. We clearly see their birth, running space, and demise. Looking at former Yugoslavia via the lens of the relationship between its socio-political identity and architectural and cultural representation – we can clearly trace its demise also via the scenographic properties of the state.

The first Pavilion of former Yugoslavia at a World Exposition was the 1929 Barcelona EXPO, where Yugoslavia broke ground with its inaugural pavilion. Dragiša Brašovan, a Serbian modernist architect, translated the brief given by the government of ‘a traditional wooden peasant house’ into an Avant-guard rendition of a black and white striped star-shaped form, which competed incredibly well with the winning design in Barcelona that year – that of Mies van der Rohe and his German Pavilion. There are urban myths that Brašovan won the Grand Prix that year, only to lose it after Mies went to each individual committee member and asked them to overturn their decision. Fact or fiction – it’s a great illustrator of what is at stake.

Yugoslavia went on to celebrate incredible successes with pavilion designs at various world exhibition events. Perhaps the best case study of this unique aesthetic vision, which went hand in hand with government diplomacy, that was already setting the ground for its involvement in the Non-Aligned Movement, was the 1958 Yugoslav Pavilion at the Brussels World Exposition by the Croatian architect Vjenceslav Richter. The pavilion won the Grand Prix that year and catapulted Yugoslav modernism as one of the great soft power tools for decades. Richter became synonymous with it and continued to produce many of the country’s trade fair architectures.

It is the last pavilion of former Yugoslavia at a world exposition, that should catch our attention in the context of discussing the relationship between statecraft and stagecraft. Even more precisely: the non-realised pavilion for Yugoslavia’s last participation at a World Exposition which took place in Montreal in 1967. The project, which is an avant-garde vision by Richter, was refused and a simplified design that was far easier understood by cultural diplomacy, was selected. This was a child-like sketch of 7 triangular structures - each representing one of Yugoslav’s nations, and one the host country. Furthermore, the selection of the cultural programme of the country’s presentation followed the return to illustrative national tendencies rather than bold avant-garde modernist themes. In 1958 one of the main works Yugoslavia selected to put onto the world stage was Bela Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin, a modernist masterpiece in the production of the Belgrade ballet. In 1967 the central dance performance was a folkloristic ensemble that happened to be touring North America on a privately funded tour by Croatian emigres.

The Yugoslav diplomacy did not travel to Montreal as the threat by Yugoslav nationalists living in Canada and North America to Tito and the country’s political and diplomatic leadership was deemed too great. The violence was rather transposed onto the pavilion itself – which was physically attacked with hammers and shot at.

The late 1960s brought an upheaval of populism and nationalism in Yugoslavia and the government decided to - rather than spend money to promote this multi-national state abroad and widen its soft power – rather focus on national production and to build monuments and architecture that reminded the Yugoslav nations of the anti-fascist struggle and internal solidarity.

I am proposing the EU Pavilion as the physical realisation of the original, forward-looking, avant-garde pavilion by Vjenceslav Richter as intended for the Yugoslav Participation at Montreal EXPO 1967. Selecting this historical (unrealised) ready-made, I propose for the EU to symbolically pick up where former Yugoslavia arrived to – in the creation of space of solidarity between nations, religions, and social spheres of its people. By staging its architectural representation as it should have happened - I propose to create a non-linear history that transcends time and political systems and rather focuses on the achievements of society in coming perhaps closer to a non-binary form of soft power but a multilateral space of discursive action and anti-populist discourse.

Diogo Passarinho StudioDE/PT

Drexciyan Pavilion

,

“Underneath the Venice lagoon awaits a coral shelter, ready to reveal itself during the current climate and economic crises, making waves within one of the most hyper capitalist art fairs in the world”

History of the Biennale/Europe

The European Union is primarily defined by its economic trades within its state members. First and foremost it benefits them, making it one of the strongest economies and safe haven for democracy, completely disregarding its privileged position and what it took from others to achieve it. Making it quite obvious, are some of the most current topics, such as the refugee, pandemic, or climate crisis. We now see Europe closing off to its shell and being crushed by a tsunami of nationalistic waves.

Throughout history, Europe’s strengthening strategy has been about expanding its borders and creating new routes; one of many examples is the “Middle Passage”, where European countries have created transatlantic highways for human trafficking. During these economic trades, more than 12.5 million people have been ripped from their places, families, and culture, only to be shipped, sold, tortured, and killed for profit.

Water has been the medium where these interactions happened and from where African slaves would see for the last time their homeland hoping to survive the journey, not knowing what adversities were still to come and we ironically see now the Venice Lagoon drowning in it. Surviving these imperialistic routes has not been the case for many and as an example, for pregnant women that were considered to be “sick” and thrown overboard, roughly a total of 1.8 million people have drowned in these impossible journeys (according to https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slave-ships-and-the-middle-passage/).

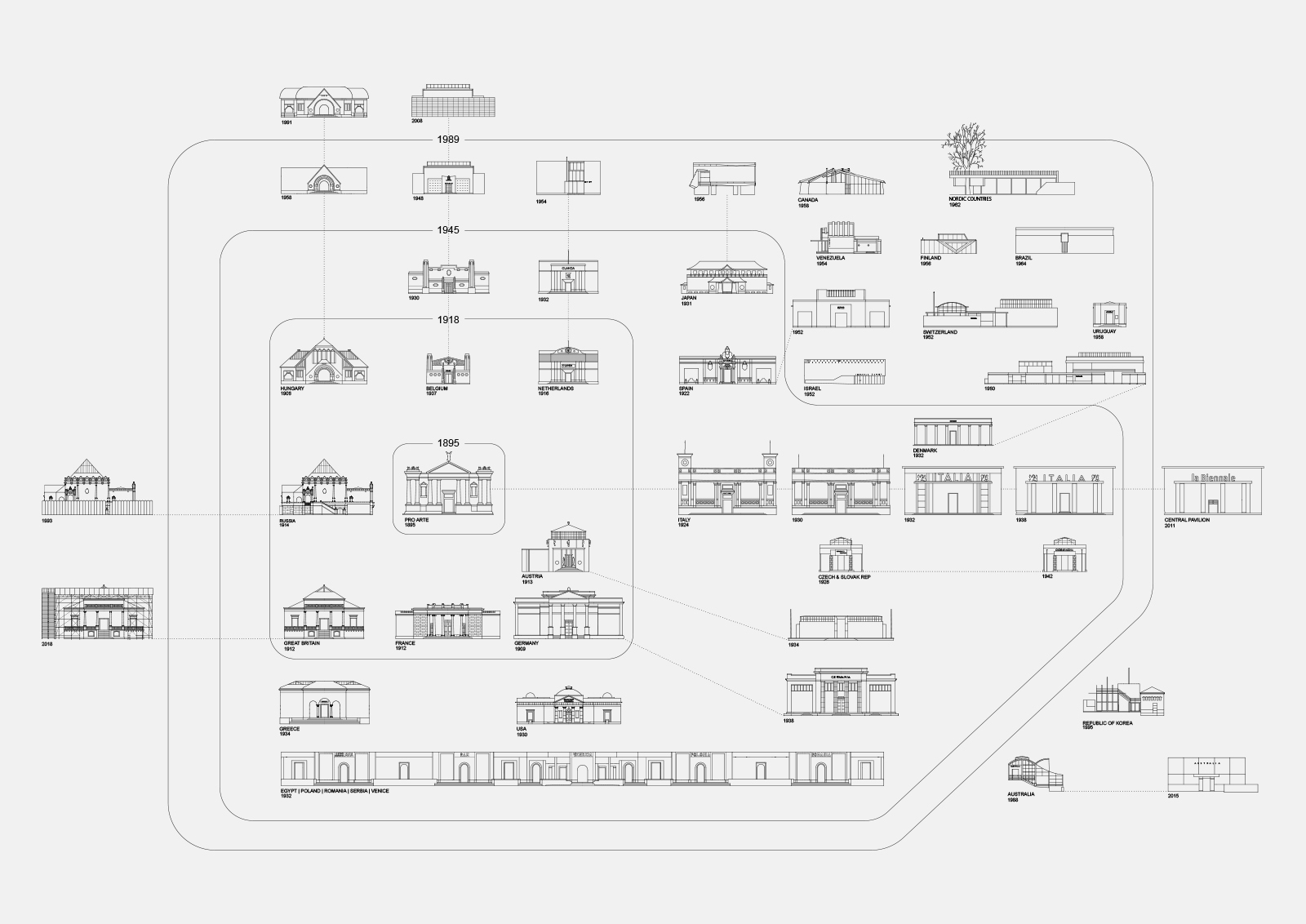

The formation of the Biennale happens exactly on the cusp moment where the enrichment through colonisation, allows European countries to still show off what has been left from these economic (rapist) techniques, and what better place to present it, than in the most famous merchant’s city in Europe. Our neighbouring partners on the site are the perfect example of this nationalistic exacerbation of power; some of the first countries to build in the biennale grounds are, Hungary (1906) Belgium (1907), Germany (1909), France (1912), Great Britain (1912), Austria (1913), Netherlands (1916) and Spain (1922).

Centrally located, the Drexciyan pavilion, is not a memorial or an homage for the people who have been slaughtered at the same time the pavilions were built but a meeting point and delayed recognition of these problematic economic strategies between these agents, that still occur nowadays but only in a more globalised realm. It is time to look forward and learn from the ones whose voices have been silenced.

Introduction

The concept of the “Drexciyan” civilisation has been initially developed through music by the Detroit techno duo, James Stinson and Gerald Donald, (Drexciya), later visually represented by the comic novel of Abdul Qadim Haqq and Dai Sato’s (The Book of Drexciya) and follow up most recently through film by the artists collective, The Otolith Group (Hydra Decapita), all of them encompassing notions Afro-Futurism.

This pavilion is conceived by a technologically advanced civilisation and built by the unborn children of the pregnant women that have been thrown overboard. For this reason, the builders and designers of this project, are unaware of what happened to their ancestors; and have been able to reclaim unknowingly the trauma of slavery imposed by the European Imperialistic practices.

The pavilion hosts these ideas and notions and transforms them into what we could imagine being an architectural representation of it. Conceptually it tries to create a stage, a shell, or a shelter for all artists, that both geographical and emotional territories have been colonised throughout history. All these nations for reasons that are obvious, had not the chance to chip in and build national pavilions that could represent them at the inception of the biennale project. We can use now this opportunity to level the ground and place them not only neighbouring their colonisers (exactly in the centre of the Giardini) but more importantly to put in the forefront of what is now a hyper capitalistic art context such as the Venice Biennale.

The pavilion is a contemplative aquatic space, completely different from the current aesthetic present in the Giardini, where different artists, thinkers, and curators, can come to express their own undercurrent voices.

Details of the pavilion

Water is not only the medium where these economic trades would take place but the only element used in the design. A solidified body of water contains a geometry very removed from the hygienic notions of the white cube/gallery space and its translucent quality brings in its surroundings creating almost a kaleidoscopic mirroring effect.

In terms of circulation, it contains no main entrance or exit, but several equal entry points, this dilutes the scenographic notion of state propaganda; where for example, most of the (first) pavilions contain a neoclassic colonnaded entry space, sometimes even composed by a staircase, all to increase the idea of ascending to a higher "state” of mind. The pavilion is grounded at the exact same level as the gardens, and its placement is surgically implemented, to make sure that no trees are damaged, taking advantage of its immediate surroundings.

Almost with non-existing boundaries, it contains a space defined by 5 interconnected pools of different sizes and depths, symbolically representing the colours and textures of our oceans and seas. From each pool of water, emerges a coral reef-shaped structure that suspends a leaf/boat-like roof. This roof is designed to melt through one gigantic skylight, filling up the first pool and subsequently all of them. The duration of the pavilion is not defined by Biennale’s art market calendar but through the current climate conditions. The same way the pavilion emerges from the lagoon it will disappear into the landscape creating zero waste, and nourishing the existing vegetation of the Giardini. Its alienated architectural language not only evokes the need to resolve the pressing social, economic, and climate issues but more importantly is based on technological novelties that so urgently need to be discovered.

Underwater tides

- Mandatory to always have more than one nation represented; mixed nationalities between participants (artists, curators, thinkers, ....)

- No artists from neighbouring pavilions, or nations that have permanent pavilions in the Biennale.

- Ideally from countries that had not the chance, for economic reasons to compete and showcase in this “arena”.

Aknowledgements

We would like to thank Abdul Qadim Haqq, Anjali Sagar and Kodwo Eshun for their support in this project.

Plan ComúnFR

A new flag & Open Air Space

,

Statement

- Before we start designing anything, we need to critically review the conditions of the European project.

- The EU -in its current shape- is an outdated device with an outdated symbol: 12 golden stars representing a pointless idea of "perfection".

- The reinforcement of the EU’s identity is welcome only if it is put to question with the objective to dismantle a history of moral superiority and radical colonialism.

- The Venice Biennale doesn’t need new pavilions to reinforce the presence and image of a global elite.

A new flag & Open Air Space

The proposal offers a new image by transforming its main symbol, the EU flag, and its translation into space for direct commonalities. This will be defined by the coexistence of 10 expressive infrastructural elements carefully placed onsite and defining a specific composition:

Foundation Stone: An artificial micro-hill, associated with a prefabricated straight stair, is built by just reusing what is available onsite -the rubbles and waste from previous events- and allowing weeds to grow over it.

Platforms: Two plinths flank the hill. They are not tables or benches. A triangular podium is located in the N-E corner of the site, the most intense in terms of pedestrian flows.

Resources: The open structure also integrates a linear water pond in between the existing trees, refreshing the air during spring and summer, an exterior kitchen -with access to free water- and a recycling point.

Open Displays: The system is consolidated with a totem to be cladded with information and a capable rail framing the intervention, integrating a roof, lightning, projection screens, vaporizers, and a display for exhibiting diverse material.

With these different devices, the proposal attempts to question the existing image of the EU, embracing beauty, plurality, complexity, and contradiction through a prototype of collective space, a resting space in the exhausting context of the Venice Biennale.

Something FantasticDE

EU Pavilion (flag, board, vitrine, bench, garden)

,

Giardini della Biennale, Venice, Veneto, Italy, Europe – or a pavilion that is not a pavilion but part of a garden:

To us, Europe is its multitude of differences. To us, Europe also is a place where everything is embedded in context. The Giardini are very European. That is one of the reasons our version of the EU pavilion does not close itself off. It rather states that it is a part of everything that surrounds it and vice versa.

It raises a (big) flag1, it provides a board and a vitrine to present a clear, concise, and unavoidable thought2, it offers a bench to talk3, and it leaves room for more garden.

We think a new European building language in essence should be one that adds; adds functions and possibility and cultural acceptance in a direct and efficient way. We think it can draw from the multitude of references that are part of its culture. We think it should be specific, and universal, heavy and light, rational and fantastic – but it should always consider its surroundings, and from those determine its articulation.

- Our proposal of a flag is not a counter-proposal to the European flag but it's rather a proposal for a second flag used on certain occasions. One that highlights the plurality rather than the unity. Something we find equally important.

- Reducing the possibilities of how to exhibit to a minimum by providing one large display board (6 meters x 4 meters) and one vitrine (1.5 meters x 1.5 meters x 2 meters) has three effects we find valuable: A. it makes exhibiting accessible (a strong message does not depend on a large budget) B. it makes it hard to miss because the message is already delivered in the open C. In its context among many others being brief is polite.

- Places to sit are scarce in the Giardini. Often however the viewpoint of someone else on a subject is what makes it interesting. The bench invites you to sit and converse.

- Although called Giardini, the nature in the Giardini is often reduced to foliage on the edge of a path. With the larger picture in mind, one more reason to be humble with the architectural footprint.

TENCH/RS

X=(Ефемерно*bewegung)

,

After an initial euphoric phase of expansion, the EU is facing increasing internal and external critique. Significant economic differences between its members have not been overcome in reasonable time. And by their own standards, the expected solidarity in times of crisis has proven insufficient. Nations from the centre to the periphery are dealing with internal efforts to exit the union. There is no shortage of crises and survival will be determined by its ability to adapt. The only certainty that can be drawn is that it won’t remain the same.

TEN considers its viewpoint on the EU from outside (Serbia, Belgrade), as well as from an enclave (Switzerland, Zurich). The EUPavilion can therefore not be simply another Pavilion in the Giardini. It has an urgency to be a radical and risky proposal.

This pavilion does not stand on its own, it requires assistance. It will not host its contents like a vessel, rather it will be bolstered by them. It does not just invite the EU to contribute its most relevant cultural findings by appeal, it straight forward begs for structural support. For each Biennale, a curator is invited to use the structure as desired. It is up to them to challenge the structure, provoke cracks, or, if aesthetically required, prompt partial collapse given the trees are not hurt in the process. All existing elements of the pavilion can be removed, altered, or copied. Each adjustment however must bear structural responsibility. The current model simulates the year 2028...

However, it does advertise unity and openness in the Giardini. It gently overarches a field of play and welcomes appropriation. Much like the EU, the pavilion emanates trust from its dear idols. The Onyx of Mies's Barcelona Pavilion has detached itself from its geological referent and displays a fractalesque process of manifoldness. On the other hand, it owes its affinity towards instability, tension, pressure, and cantilevering to early constructivism. And chances are high, that in ten years time it stands in the water due to the rise of sea levels and it can be explored by a barge.

Evita VasiljevaLV

Energy Bank

From the perspective of a Latvian girl able to join the Erasmus program in Berlin in 2009 four years after Latvia joined the EU, the EU seemed like a miracle. Everyone was together, mixed, united, and kept their own identity. It seemed a perfect self-organized organism, constructed and open.

If the European Union would be a building, it should have plenty of light and air. The roof would be the main element that holds everything together. The glass is custom-made, bluer, and greener than the glass we know. It is more glass (to realise this model I used glass from recycled windows). It is a subtle way to show that the window is not just a means to see through. Mistakes should be included in the structure. The Shape should have a strong character. The layout of the space should have a self-mirrored layout, a positive and a negative of itself. The front should look like the back and the back like a front. There are two entrances or two exits.

The title of my proposal is Energy Bank. It's the title I use for self-mirroring/self-sufficient/self-perpetuating structures. It suits the idea of the EU as a self-organized place with an appearance to be open for everyone. William S. Burroughs inspired me for the title. A long time ago I read an essay, in which he used the phrase "Thermodynamic pain and Energy bank" to criticise contemporary art as an enclosed and "self-feeding" structure. At the time I thought his criticism was rather inspiring.

EUPavilion Eight proposals presents eight projects for the first European Pavilion at the Venice Biennale proposed by European artistic and architectural practices. The participants were invited by the curators of the exhibition to reimagine the national pavilion

, still today the dominant symbolic and spatial paradigm within the GiardiniStudy for a Pavilion, Giorgio de Vecchi

.

At the same time, the project for the European Pavilion provided an opportunity for asking what new representative languages are needed for defining the identity of a supranational organization in a state of continuous crisis and perpetual construction like the European Union. In the light of the current debate around the strengthening of the European integration, a reconsideration of the spaces where this process happens is of critical importance for the definition of a democratic and inclusive public realm.

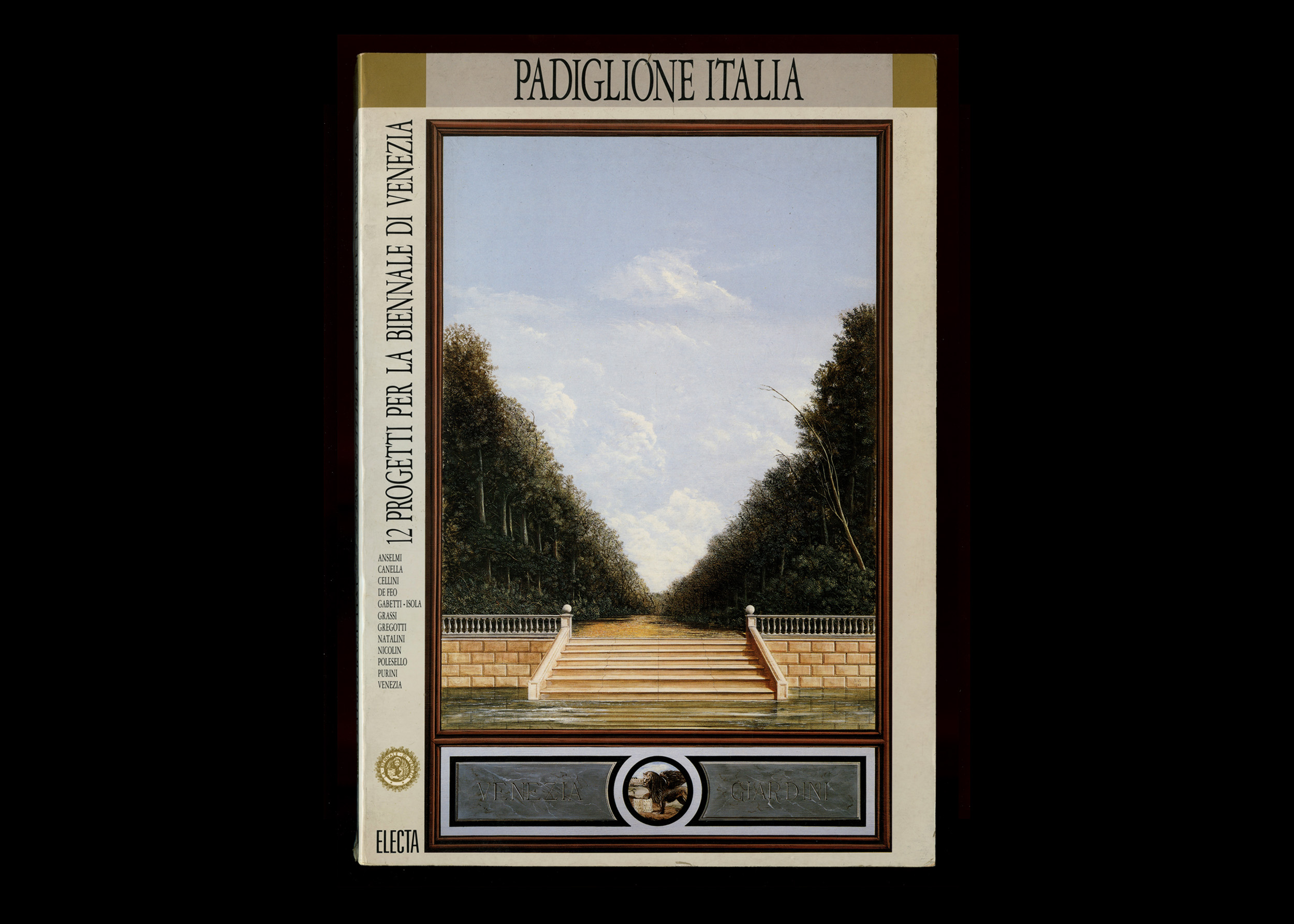

With its long-standing tradition of exhibitionsStarting from the renowned Strada Novissima by Paolo Portoghesi in 1980, the Biennale has commissioned architectural projects on various occasions. Some of these exhibitions were based on actual needs and development projects of the Biennale spaces, like the Padiglione Italia competition in 1988, which saw 12 prominent Italian architects reflecting on the reconstruction of the Central Pavilion in the Giardini as a modern museum facility for the city of Venice.

Some other had a more speculative approach, like the very first international architecture exhibition organised by the Biennale in 1975: “A proposito del Molino Stucky” which presented theoretical proposals for the massive brick building

based on an architectural brief the Venice Biennale and the typology of the pavilion provide an ideal testing ground for a new kind of European public building.

The variety of approaches and responses provided by the participants – who grew up both within and on the borders of a Union under construction – reveals the extent to which architecture constitutes fertile, albeit little used, ground on which to develop the debate on European integration as a cultural project. The EUPavilion project aims to raise awareness of the public on these issues, by means of design.

The eight projects for the European Pavilion at the Venice Biennale are illustrated by means of 1:20 scale models, filmed and scanned by No Text Azienda, and photographed by Delfino Sisto Legnani.

EUPavilion is structured as a research laboratory exploring the relationship between architecture and European institutions. The laboratory is working with a number of partnersIuav University of Venice, Europe City Project, BookBiennale, developing its research through the organization of public eventsTowards a European Architecturein the framework of Europe City Milano festival in May 2019, EUPavilion curated “Towards a European Architecture” a public debate between architects and urbanists Stefano Boeri, Paola Viganò and Pier Paolo Tamburelli hosted by the Triennale di Milano, academic activitiesin July 2019 EUPavilion was invited to run a workshop during W.A.Ve. 2019 at Iuav University in Venice

and publications[1] The Giardini of the Biennale di Venezia. Dialogue and Clashes between National and International Aspirations; [This essay was originally published on “Supervenice” Vesper, Journal of Architecture, Arts & Theory No. 1, Fall-Winter 2019, Università Iuav di Venezia, Dipartimento di Culture del Progetto. Quodlibet ISBN 9788822904164] Designed by Giannantonio Selva at Napoleon’s behest in the early nineteenth century, the public gardens, a characterising element of the bourgeois city, constitute an instance of radical discontinuity in the Venetian urban fabric, which quite naturally changed into the free territory destined to accommodate the cultural embassies of the countries that joined the International Art Exhibition during the 20th century. This free zone was open to architectural experimentation, but it has also become an inter- national stage on which we continue to uphold, first and foremost, ‘the importance of being there’. The geopolitical transformations affecting the Western world during this same period had a fundamental impact on the relationships between the pavilions and the evolution of their languages in the framework of a continuous conflict between the desire to affirm national identities and international aspirations.[2] Il faut être absolument européen!; [This essay was originally published on the catalog of the 2019 summer workshops held at Iuav University in Venice: W.A.Ve. 2019 Venezia città sostenibile edited by Marco Ballarin, Daniela Ruggeri, Anteferma Edizioni 2020 ISBN: 9788832050714] The relevance of Venice in the international cultural scene constitutes one of the main characters of the city. We believe that this specific vocation – typically embodied by the Biennale – could open the way for a "sustainable" urban project. Thus, we propose to focus on the spaces of production of culture, critically reconsidering the Giardini della Biennale – the place of origin of the cultural vocation of Venice – through the design of a new type of Pavilion. The National Pavilions inside the Giardini della Biennale are bound by relationships that allow a clear reading of the historical development of the site and present through their form a vivid image of the political will of the nations that built them at that very moment in history. Such anachronistic relationship calls for a new model of pavilion that goes beyond the national paradigm. The project of a European Pavilion for the Biennale will have to tackle this issue, trying at the same time to reflect on the relationship between the European institutions and architecture and the meaning of a European “monument” while relating to some of the typical characters of the European historical city of which Venice is a paradigmatic case.[3] Architecture and European identity. A conversation with Romano Prodi[This essay was originally originally published on Ardeth n 7. A magazine on the power of the project: “Ardeth #07 EUROPE. Architecture, Infrasturcture, Territory”, Rosenberg & Sellier 2020] The purpose of EUPavilion is to reactivate the debate on Europe as a cultural entity and not simply as a political-economic union. This debate, which enjoyed a particularly lively moment around the year 2000 concomitant with the introduction on the single currency and the eastward enlargement of the European Union, came to a stop with the failure of the European Constitution project and was definitively overwhelmed by the arrival of the 2008 economic crisis. Now with a view to restarting the process twenty years later we thought it would be useful later to revisit some of the key events of the time with Romano Prodi, the Italian politician who more than any other contributed to consolidating the European integration process. This website is conceived as the growing archive for the materials relating to these activities. EUPavilion is a collaborative effort that brings together architects, scholars, photographers, designers.